For the 100th anniversary of the birth of Ludmilla Otzoup-Gorny, better known as Madame Ludmilla Chiriaeff, the Société d’histoire de Rawdon wants to highlight the presence and contribution of Madame Chiriaeff and her family to the wellness of the population in Rawdon.

In addition to her achievements in dance at the provincial and national levels, Madame Chiriaeff shared part of her private and family life with Rawdon’s population. With her husband, Alexis Chiriaeff, with whom she emigrated to Canada, and later with her new spouse, Uriel Luft, Madame Chiriaeff spent a lot of time in Rawdon along with her daughters Anastasie (Nastia), Ludmilla (daughter) and Catherine (Katia) and sons Avdé and Gleb. The following is their Rawdon story, as told by eldest daughter Nastia… and corroborated by Katia and Avdé.

Ludmilla Chiriaeff in Rawdon: a summer family haven in her early years in Canada

Article written by Anastasie Chiriaeff in collaboration with Katia Mead and Avdé Chiriaeff, May 2024. Unless otherwise specified, all photos are courtesy of the Chiriaeff family, all rights reserved.

Arrival in Canada

It was January 26, 1952. My first memory of our arrival in Canada, more specifically in Halifax, is of seeing my parents, Alexis and Ludmilla Chiriaeff, having to leave the room where my brother Avdé and I were waiting for them to settle some official papers. The wait seemed interminable. I was three and a half, Avdé was one.

My mother was more than eight months pregnant. Our brother Gleb was born exactly one month later; he was the first in the family to become a Canadian.

We were expected to be resettled in Toronto. So, we left by train for the Queen City. Once there, with the welcome not being what we had expected, we quickly retraced our steps and headed for Montreal. “People speak French there!” my mother said.

On our way back, my mother marveled at the beautiful landscape we were traveling through. It was winter, snow was falling, and the wind made the snowflakes dance; it all reminded her of the Russia that her parents had described to her as a child, this country they had had to flee because of the revolution, and that she never knew.

Her father, Alexandre Otzoup-Gorny, an engineer by trade and a prolific writer and poet, had depicted his homeland so vividly that she felt as though she were there as the landscape streamed by. He had passed on to her the magic of words that made everything our senses perceive come alive.

She said that she felt a deep sense of peace and certainty that Canada was where our lives would unfold. The parents, stateless, would finally have a country of their own!

Integration into the new life in Montréal and beginning of Radio-Canada, schools and company

When we arrived in Montréal, my mother went to look for a hotel for the night. Turning the corner on Sainte-Catherine Street, she noticed a movie theatre whose marquee, all lit up, announced the film that was playing there. To her astonishment, it read:

« DANSE SOLITAIRE »…and her name LUDMILLA OTZOUP GORNY...

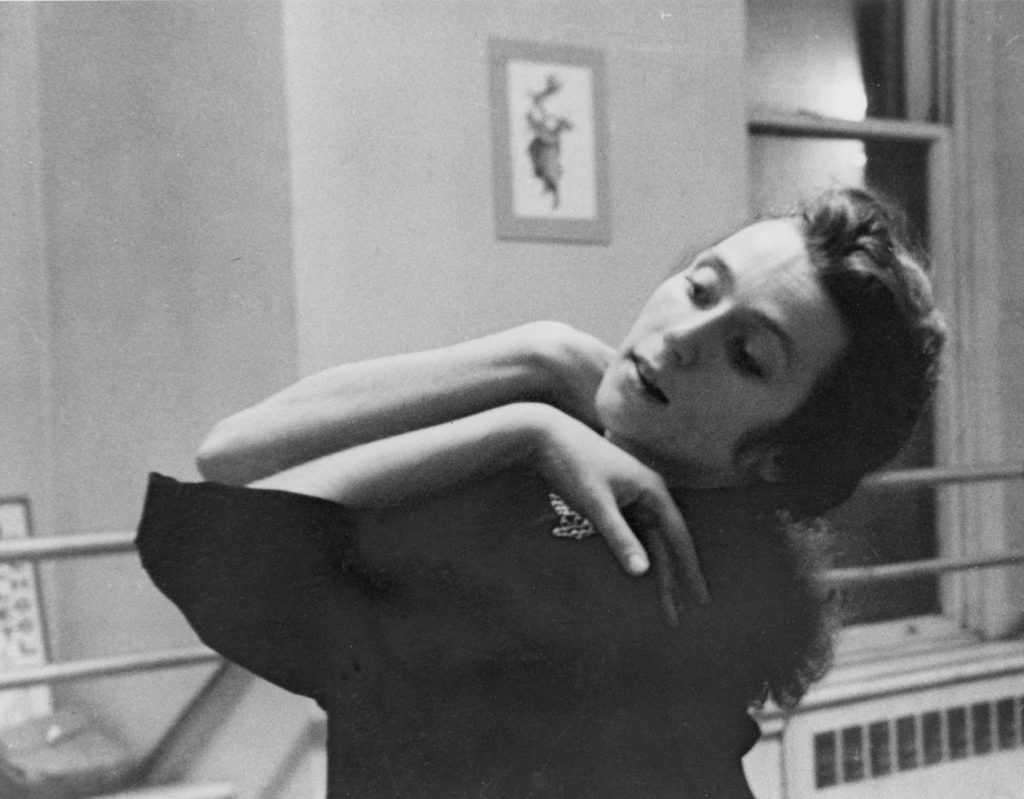

It was a film she had danced in, and her uncle Georges Raïevsky was the producer. Right after the war, when she was a dancer at the Geneva Theatre, she had taken part in a few films, including the one that was playing when we arrived in Montréal—another sign, she said, that confirmed we were surely in the right place, the right city!

Throughout her life, she had had moments like this that appeared to validate her path and decisions.

When we arrived, Montréal was a very lively city, unlike Toronto at the time. The parents soon learned that Radio-Canada, which had just opened its doors, was starting to recruit artists for cultural programs.

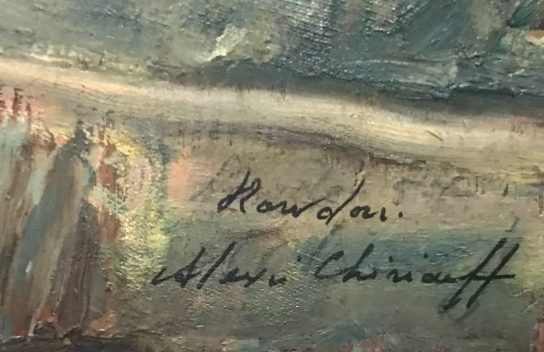

My father was a painter and was hired as a set designer, a career he pursued there until he retired. My mother was hired as a dancer and choreographer and, during her time in television, she staged over 300 works. It was the beginning of two exceptional careers.

Having recruited a few dancers for the television programs, my mother formed a small troupe, Les Ballets Chiriaeff. At the same time, she opened her first studio to teach ballet.

Over the years, her troupe grew to become Les Grands Ballets Canadiens; and her school, Ludmilla Chiriaeff Ballet School, on Union Avenue, became the Académie des Grands Ballets Canadiens and finally the École supérieure de ballet du Québec, now located at the Maison de la danse on Rivard Street.

Beginnings in Rawdon

Meanwhile, my brothers and I began attending school, and taking ballet, music and Russian language classes.

Indeed, every Saturday, we would go to the parish school of the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Cathedral, the oldest Russian Orthodox parish in Montréal, where we would learn Russian grammar and literature, Russian history, and Orthodox catechism. It was very important to our mother that we not lose our slavic heritage.

Our parish priest was Father Oleg Boldireff, who officiated mass, headed the Russian Saturday school and had a family cottage in the countryside, in Rawdon.

Once settled with his wife and five sons, he built a small chapel on his property with the help of his parishioners and my parents.

The chapel was made of logs and had an onion dome steeple, typical of Orthodox churches. During mass, we would stand, holding a candle.

And that was how we were introduced to our beloved Rawdon.

The walls were adorned with icons lit by lanterns. The altar was hidden behind a partition, with “celestial doors” in the center, decorated with biblical scenes painted by my father, who was commissioned to reproduce them according to tradition. The choir sang the liturgy a cappella, and Father Oleg would pray aloud in Old Church Slavonic, swinging his thurible and blessing us. It smelled of beeswax and of sweet incense. All of our senses were awakened.

Rawdon as a family and in the Russian community

At first, in the summer, we would go to visit Father Oleg Boldireff, as did many parishioners from Montréal. Very soon, we too wanted to have a cottage to spend our vacations there.

Made entirely of knotted pine wood, our dacha was very modest, but for my parents and us, the children, it was our little heaven on earth.

Once we were settled, dancers from the troupe would come to visit us on Sundays. My mother loved to entertain, both for pleasure and often for work. It was at that time, as well, that she went to give ballet classes at Rawdon’s town hall and even at the home of the Pontbriand family, of which brothers Henri and Jean Pontbriand played a central role in the development of the village and the region.

Our parents worked in Montréal during the week and would come on weekends to enjoy nature and rest.

When it rained, we would go out to gather mushrooms; we were taught which ones were edible and which were not. My mother would clean them and dry them to eat in the winter or cook them the same day.

My father would leave with his paintbrushes and tubes of oil paint and return in the evening with a painting or two of the magnificent nature surroundings.

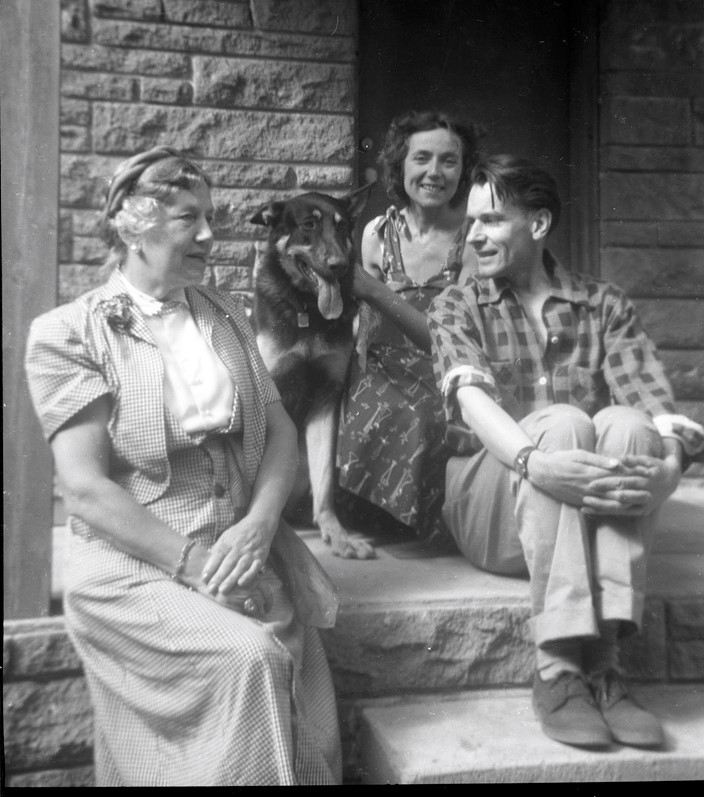

Our maternal grandmother, Catherine Otzoup-Gorny, made jams from berries we would pick as well as “nalivki,” an alcoholic liqueur. Those were the days when the village baker would come around to sell our favourite bread called ”pain de fesses”, a double loaved bread, from his horse-drawn carriage, and when we had blocks of ice delivered for our icebox to keep our provisions fresh during the summer.

Our street, 17th Avenue, was a dead-end road surrounded by a rich, dense forest. Many young Russians came to play there and get back together with their summer friends and neighbours.

We spent all our vacations there with our parents and grandparents.

This is how we lived and shared our “Russian-ness,” as we were surrounded by adults who spoke and sang in Russian, who cooked traditional dishes, and told us about their memories of the land of their childhood.

Grandmother Catherine was among those who would say that Rawdon was a veritable little Russia, with its birches, mushrooms, strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries. She felt at home there.

It was during her visits that she would tell me a bit about her childhood and her journey all the way to Canada.

She was born into the Polish aristocracy, into the Radziwill family, but life’s circumstances were such that she grew up poor with her mother and sisters in Saint Petersburg.

When the Bolshevik revolution broke out in 1917, she had to flee and followed the Russian diaspora to Europe, with her husband, my grandfather Alexandre Otzoup-Gorny, and their eldest daughter, Valentine. My mother Ludmilla, born 10 years later, grew up in Berlin, among Russian émigrés, many of them artists and intellectuals awaiting the fall of communism to return to their motherland. At school, she studied half the day in German and half in Russian, to be ready for an eventual return.

The Second World War uprooted the family once again. When the USSR emerged among the victorious allies, they realized that communism was here to stay, and that their dream of returning to Russia was unattainable in their lifetime. The loss of that dream was a hard blow, but it enabled them to seek out their future on a new continent.

Grandfather Alexandre died in Madrid before the family could immigrate. Grandmother Catherine finally found refuge with her daughters, one in the United States, the other in Canada.

Grandmother Catherine was from another time. I would see her sitting on the small porch of the house in Rawdon, a Russian newspaper in hand. Dressed to the nines, she wore an ensemble with a lace blouse and ruffles. What little hair she had was pulled in a bun with a braided crown on her head and over her face she wore a fine black veil held by two pins stuck into her bun. When she went for strolls, she protected herself from the sun with a parasol. She walked with grace and dignity. In my eyes, she looked like a tsarina. |

Father Oleg Boldireff liked to organize evenings around a campfire, where we would sing our traditional songs, and he, with his sons, would sing those of the Cossacks. Other families continued these festivities at a camp called CROFI (Canadian Russian Orthodox Foundation Inc.), a Russian summer camp, not far from our home.

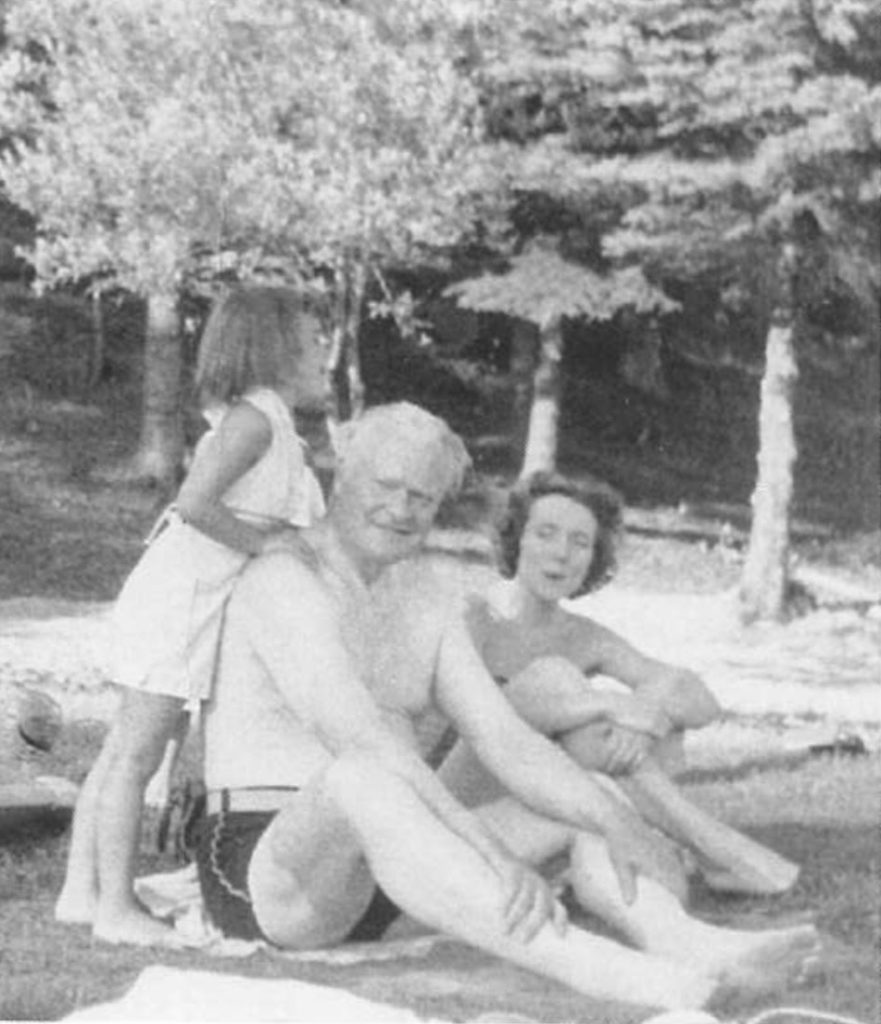

Summer after summer, we would meet up again to spend time together, and our outings included going to the municipal or the Pontbriand beach. We would spend the day swimming and fishing. My mother often cooked a fish we brought back. She herself would accompany us to try her luck. She would prepare snacks for the day, and we would come back in the evening, happy and tanned.

Our activities with the parents would take place together and in Russian.

It was a magical family time. Rawdon had become a very special family place—our “Madeleine de Proust.”

Later, when the parents could no longer come with us, we would go there with nannies from the community. It was also where she was able to find employees for her ballet school. There was an accountant, a receptionist, an administrative assistant and a couple of janitors, all members of the Russian community living in Rawdon, some even on our street.

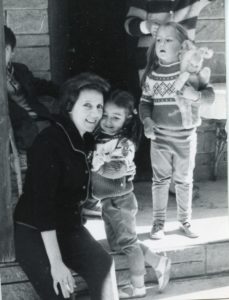

When my mother remarried, with Uriel Luft, they had two beautiful girls, my sisters Ludmilla et Katia Luft, one blond with blue eyes and the other very dark-haired with brown eyes.

They too spent their summer vacations at the cottage for quite a few years. I was 15 at the time, and I had the pleasure of sharing several summers with them. I passed on to them our beloved Russian traditions, learned from the adults who had surrounded me during my childhood. We would spend hours gathering mushrooms and cooking or marinating them. We would make bread and prepare jams after having picked wild strawberries or raspberries. We would take walks in the woods to gather flowers or leaves and make collages. At night, during thunderstorms, we would play cards and listen to the raindrops splash down on our roof. My mother would say that this sound was the divine rhythm.

When the parents came on weekends, we would present a mini exhibition of drawings, collages, and paintings, created by the sisters and their young friends.

We were steeped in creativity, all thanks to what my mother had transmitted to us…all her descriptions of the creative activities of her childhood with her parents, especially her father, and all those she organized for and with us.

As such, Katia and Ludmilla (Luft) also inherited the old Russian culture, preserved and lived by generations in Rawdon. And now that they are parents themselves, this family legacy continues to be passed on to their children.

For years, we would go to the cottage all together, but over time, work meant that visits became rare. When I was 21, my parents bequeathed the house to me. We would then share our vacations in Rawdon and elsewhere.

As our cottage was not winterized, we occasionally spent Easter vacations at the Rawdon Inn.

That was how we met Mrs. Rochon, the owner, and her nephew, Richard Rochon. He was our age and became a family friend and has remained so to this day. Having been in contact with the Russian community during his youth, he was drawn by this community and later chose to learn Russian and study to become a Russian Orthodox priest.

Administrator of the Saint Seraphim of Sarov parish in Rawdon for many years, he went on to become the Archbishop of Ottawa and the Archdiocese of Canada, among other roles.

Mass was celebrated every Saturday evening and Sunday morning, and my brothers Avdé and Gleb, with other boys from the community, were altar boys. As for me, I sang in the choir. My mother attended as a parishioner. She did not go to church regularly, but she was very devout and spiritual.

We would participate in the religious ceremonies that would take place there, sometimes for weddings, other times for funerals. During holy celebrations, tables were set up on the property of the Boldireff family, and everyone would bring a dish, a family recipe. My mother would join in when she was visiting, preparing dishes of her own. Both children and adults would sing our traditional songs.

The chapel, with its celestial doors, is now located on 15th Avenue, next to the Russian cemetery.

In 1962, our grandmother, Catherine Otzoup-Gorny, was the first adult to be buried there.

We have since laid to rest there our mother, Ludmilla Chiriaeff, in 1996, my father, Alexis Chiriaeff, in 1999, and then our brother, Gleb Chiriaeff, just recently, in 2023.

For my brothers, my sisters and I, Rawdon was a corner of the world where we spent some of the happiest moments of our childhood as a family. For the parents and grandparents, undoubtedly, it was a sweet reminder of their country of origin. And for our mother, it was all that and a haven of tranquillity from a very rich and full life that she lived thoroughly until her final days.